'Out With Lanterns', by Christie Cochrell

“I am out with lanterns, looking for myself.”

-Emily Dickinson

The Book Bag

Feeling fragile lately, and strangely discomposed, not wanting to do anything but read for

days on end, I finally summoned enough energy to walk down to our little beach, down the lagoon.

Watching the playful in and out of waves, letting my eyes follow their constant unresisting erasure

and travel on, further, to the vanishing point, I realized that I have been here too long. Stagnant

and dull, and not myself.

I took with me one of the paperbacks I still couldn’t put down, a lifeline to some other

world, along with a notebook and pen, of course, in a canvas book bag. For this small pilgrimage,

the bag had to be that bag, only that one would do. An elegant navy and chalk white, printed in a classic

typeface with serifs: London Review of Books. The excursion with shoulder bag in lieu of steamer trunks

felt like an important gesture of defiance, somehow, as I ventured out against my jailor’s will—in

this case the lethargic me, reduced almost to tears by the feeling of having lost things I have had and

been, elsewhere, at other times. Things I am terrified of letting go—however often I assure myself

that they’re safely preserved, having been tucked into journals and stories the way piñon nuts or the

crushed pods of cardamom are folded into rising bread dough and blessed quietly with a teaspoon

of Cretan thyme honey.

That particular bag, I’ve realized since I wrote it down, holds in its fabric something essential

of me, inseparable from where and how I found it.

Like Souls

Four years ago in May, I was able to explore London with my husband most mornings for a

couple of hours, since we couldn’t go to see his mother in the hospital until mid-afternoon. Our

visits to her northern borough had always been circumscribed—time and attention spoken for,

thoughts not our own, but at chance moments slipping out through loosened slats of kitchen blinds

to trees and sky, and the imagined spans and spires of the nebulous city beyond.

The day I slipped off to Bloomsbury on my own, I happened across the London Review

bookshop and cake shop—both exceptionally fine and as I knew England should be, reminiscent of

my long acquaintance with its literature, culture, history. I had to sternly stop myself from buying

more than six or seven books, my suitcase already bulging. Around me in the café were kindred

spirits: writers, a language professor and woman clergyman discussing variously evensong, Chester

Cathedral, transcribing, and Georgia 11 pt. type. Bookish and civilized, exactly what I needed. My

early lunch was tomato and emmental quiche, along with two inspired salads—kale and broccoli

with guacamole and toasted sunflower seeds; and white quinoa with fresh herbs, green olives,

spinach, and chermoula dressing. White peony and rosebud tea finished gilding the lily.

Later I passed a shop selling pigments, resins, and drawing inks, then found white lilacs

in Bloomsbury Square. They evoked childhood lilacs, lilacs brought to Santa Fe from France by the

archbishop of the Willa Cather book. And, too, the wistful yearning T.S. Eliot conveys so well,

sometimes with lilacs. The host of writers and artists gathered over my lifetime was with me, the

company of kindred spirits including all of those favorite novelists famously drawn to England,

Paris, and Italian hilltowns, finding the old world more persuasive than the new, the foreign oddly

more familiar.

Always the words accompanied me, with their magic. They drew me

another year, against the odds, all of the way across London to Kew Gardens—

in quest of lilacs once again (if late, in their last bloom), but more than anything

to find the grass garden mentioned by Michael Ondaatje in The English Patient,

which I’d added to a notebook recently, coincidentally in the context of identity,

its loss and changeability.

“They unwrapped the mask of herbs from his face. The day of the eclipse. They were waiting for it.

Where was he? What civilisation was this that understood the predictions of weather and light?

El Ahmar or El Abyadd, for they must be one of the northwest desert tribes. Those who could catch

a man out of the sky, who covered his face with a mask of oasis reeds knitted together. He had now

a bearing of grass. His favourite garden in the world had been the grass garden at Kew, the colours

so delicate and various, like levels of ash on a hill.”

I’d given up all hope of getting there at all—even by underground, much quicker than the

riverboat with burnished oars I had imagined carrying us down the Thames—but the very last day,

midafternoon, we stole a few hours and went to Kew.

And that contrariety somehow made me myself again.

Stolen Time

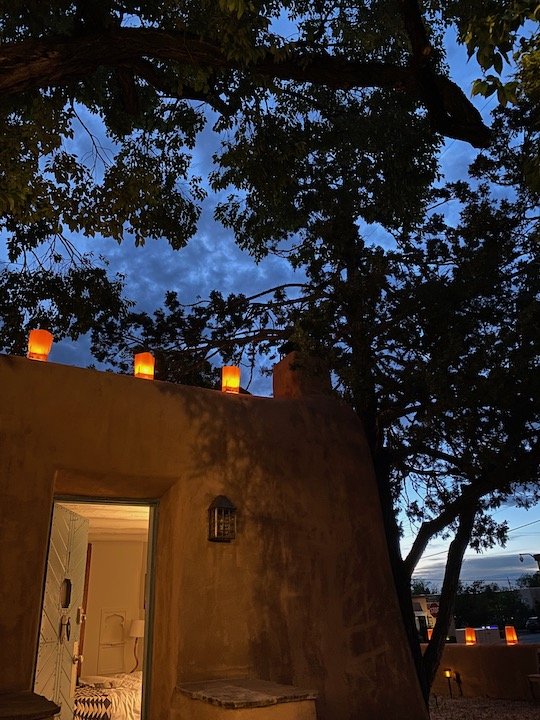

More stolen time, precious for being rare. This a few years before, in Santa Fe, another

hospital—what would be the last visit with my own mother. In early mornings before the heat rose

I’d park along the river (nothing like the Thames or Seine) and walk to the teahouse on Canyon

Road, the street of artists, where I’d sit and write in a garden of apricots, green pears, remembering a

summer long before, reading Colette and sitting in the shade with my father pitting a deep bowl full

of tiny cherries from the trees behind the patio so my mother could make a tart. I walked up

Canyon Road one afternoon to one of many galleries with low ceilings and wooden floors, to see the

photographs of André Kertész, black and white photos of Paris, adding to my

nostalgia for far-off places that were yet somehow there in Santa Fe’s

aura. My feeling that I was, in some strange way, practically there.

Or I would walk the outdoor labyrinth with blue foothills and mountains in

the distance on all sides, and an uncanny echo at its heart. Outside the Folk Art

Museum, not far from where I went to school. I followed the stone turnings of

the labyrinth barefoot, one meditative round after another, in and out, and in

and out again, before the museum staff got to work and saw me, found

my bare feet, and my sacramental aspect strange. Before I headed off to my

duties of care, resumed my customary role.

During each of those hours out of bounds I found myself again, ever so

briefly; found ways of not letting circumstances define me. Define comes from

the Latin noun finis, meaning boundary, end, the limit of. It’s closely related to

confine. Its sense conveys my tendency to be—or seem to be—what others want

of me. The way I fit in, passively. The way I then have to rebel, break away from confinement

and unwelcome definition, to reclaim what’s best in me. (That child I was who

inexplicably delighted in smoked octopus, Portuguese stamps, obsidian.)

Sort of Weird

Years ago, for a writing class at Stanford in the early 90s, I wrote a pensive creative

nonfiction piece exploring obliquely my struggles with identity. A triptych, a three-faceted shaping

of the gemstone I imagined I might be.

I. I like the Laura Gilpin photograph best of everything at the Georgia O’Keeffe exhibit at

the Legion of Honor, better even than the utterly purple—almost black—petunias, the drenched

colors of the other flowers. It seems to me a perfect portrait of the artist, though she isn’t actually

in it—a portrait of those things that have made her what she is—which names the exhibition, The

Poetry of Things. A row of oil paints in silver tubes, paintbrushes of various widths and bristles, a

horn curved like an elongated ‘S,’ a little puddle of river rocks, the Abiquiu desert country beyond.

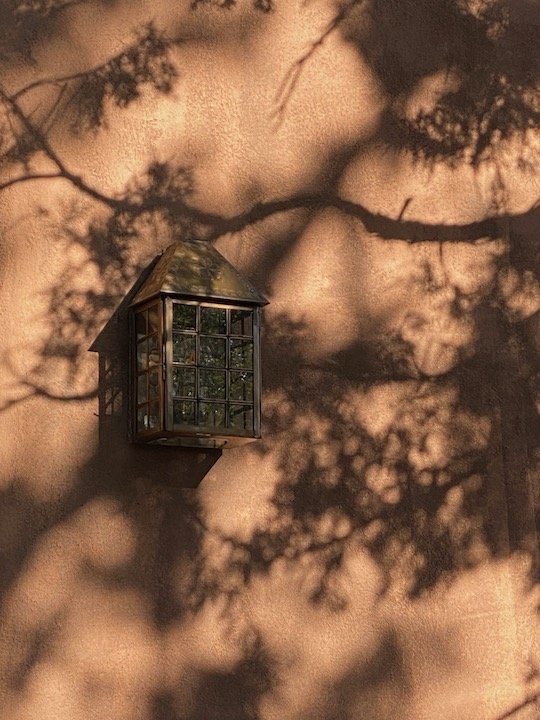

Other paintings and photographs record a little track of sunlight across an adobe wall; the

covered well inside the patio where the artist grew desert sage; shells and white bones from the high

desert, once the bed of an ancient sea. These bleached things are restful but evocative, like the

Greek temples with their garish paint worn off which we like to believe were intended that way.

All these things remind me of a past like a mirage, a shimmer on the road away.

II. This summer I went to Taos for the first time, though I grew up only two hours away.

I’d always been led to believe it was prohibitively far or hard to get to. I grieved for the aching

absence of that place I’d spend my life learning to fill. I didn’t understand why I’d been kept from a

part of myself, so long.

“Why didn’t we ever go to Taos?” I asked as soon as I got back.

“I never liked Taos much,” my mother said. “It’s sort of weird.”

As am I, Mother, I would have said, if I hadn’t been schooled to give in, go along.

I came back upon myself that day, as I do sometimes unexpectedly. Out with my lantern,

with my greedy, fetching pen.

I took pictures of turquoise doors in early afternoon, and bought a bar of soap with juniper

berries, then drove out to the D.H. Lawrence Ranch—five miles of dirt road in from the highway in

a canyon north of town. (I’d later describe the visit to the ranch of the author transported to New

Mexico from England as the best part of the day, which, feeling guilty, I had almost

skipped—already later getting back to Santa Fe than I had promised.) The ranch was given to

Lawrence’s wife Frieda by Mabel Dodge Luhan, whose spinach enchilada recipe I’ve got

somewhere, in exchange for the manuscript of Sons and Lovers. His ashes are there, brought back

from Italy on a freighter and mixed into the concrete of the rustic altar of his shrine so neither of

the women fighting over them could steal them to scatter elsewhere. His typewriter sits slaked with

words inside the window of his pine and adobe cabin. Silent. Spent.

The poetry of things. Alone except for a couple whose dust and New York license plates I

followed up the canyon from the highway, passing cottonwoods and rabbit brush and sage and high-

piled thunderheads, I took pictures of the buffalo painted across one of the outside walls (like

Lascaux, I noted), of the blue bench under the high pine tree where Lawrence sometimes wrote or

sat and looked up into the cathedral-tall branches that Georgia O’Keeffe later painted when she

stayed in the cottage.

Her painting of that pine was in the show at the Legion of Honor. We got so close there, for a

minute, years apart.

But back in Santa Fe I was unsure again. And unforgivably late.

III. Maybe I will live in New Mexico again someday, but on my own terms. I’ll take the

fossil fish that’s on my writing desk, the white shells from Cape Cod, my Greek octopus pot, the

postcard of “Black and Purple Petunias.” Maybe I’ll regret what I’ve become, here in exile, when I

look back. Maybe I’ll even choose to live in Taos. In any case I’ll frame the photos I’ve taken of the

church of Ranchos de Taos and the monastery high above the sea on Santorini—so remarkably

alike. Those worlds I never knew were possible, that are native to me.

Maybe someday I will bleach too, like the pieces of wood and bone the artist loved, and maybe

then, maybe in my old age, I won’t seem weird any more—or will at least stop minding that I

irrevocably am.

—

But twenty-three years later here I am, still weird—and needing to affirm it. Sitting on a

bench a stretch of sand away from the Pacific Ocean, reflecting on Bloomsbury and Taos and

writing classes at Stanford. Thinking of being kept from my true self, again. No matter that I really

like this little beach, that many of my travels have been to islands, bodies of water, distant seas. This

sea. No matter that I’m happy for the most part, staying put, surrounded by old books and artifacts.

Only I find it’s not enough, sometimes. I need something unusual, again, always.

And the ante has been upped. Retired now, my various careers behind me, both our

mothers gone, and travel feeling more and more impossible, given our age group and the new health

risks, I have to wonder if this isn’t about it—if any crucial pieces I’m still missing are just going to

have to stay out there somewhere, unclaimed. If the rest will be silence, attrition. That’s why I’ve

grabbed my London Review bag today, clung onto it and its contents for dear life. I need the

possibility of unexpected booktroves, and maybe a little orange and almond cake, to add to all the

words already secreted away (some tumbled river stones, some light-catching obsidian, some lapis

lazuli ground into purest blue). Of rabbit holes and rabbits out of hats, the magic which venturing

out of the familiar invokes.

Wayward

All my recent excursions have been into the byways of words, collecting whatever lexical

felicities happen along. Weird has been one. In late Middle English, as wyrd, it first meant

“fate, fortune, or chance.” What happens to me, beyond human control; whatever quirky offerings I

chance upon. Offerings of things out of my ken, maybe. Of chermoula and cobalt green pigment,

along with more familiar rabbit brush and sage. Of a Greek travelogue in paperback by Patrick

Leigh Fermor (who packed a volume of Horace and walked to Istanbul instead of university; lodged

in a Benedictine monastery, swam the Hellespont, and built a house in the Peloponnese, where after

lunch he’d sing in Hindustani “It’s a Long Way to Tipperary”). And some months later a chance

recipe for Patrick Fermor’s moussaka, with aubergines, courgettes, potatoes, a cinnamon

stick—leaving me wanting dinner guests. All of that ending up in a notebook, some miscellaneous

writing that’s turned up again here.

But by the 16th century, that meaning of wyrd was extinct in English. The noun survived in

Scots with its meaning of “destiny, one’s appointed lot; a god’s decree or prophecy.”

Writing his Scottish play, Shakespeare happened upon it there, and stole it back to name the Weird

Sisters, the Three Witches—thus bringing it into English again, but with new connotations and a

formal new meaning, given the context of this fateful christening. Weird meaning “abnormal or

strange” (those things I am) came into use after Macbeth, with a dash of word-carried witchery and

prophecy added.

Shakespeare originally called the Sisters Weyard or Weyward, and I can’t

help thinking wayward (“difficult to control or predict”) despite any absence of

proof, describing my progress through life. That brings to mind as well long-lost

wyrd’s meaning in proto-Indo-European—“to turn, wind, twist.” Again perfectly

describing my perambulations through those neighborhoods of cobblestones

and lilac-heavy squares. Or other times into the heart of the turning or winding

labyrinths, whether at Knossos or in Santa Fe, at Stanford or Ghost Ranch.

So the various senses of weird are in me, and, all interwoven, take me on a

magic carpet ride. Not humanly determined. Determined by fate at large, by

witchcraft or the Fates (writ large), who were mentioned by name in another

archaic usage of the word. Invoking the three weaving goddesses who assign

individual destinies to we mortals at birth.

In my long novel set on Crete, the narrator, who might call herself weird, tells her own story

in the guise of Greek mythology.

“I remember the first time I watched the weavers in Chimayo (New Mexico, where I grew

up): amazed at how the colors worked themselves into a pattern through the simple motion of the

wooden loom. I stood in the doorway mesmerized, wanting so badly to figure it out. Those were

the Fates, spinning my destiny. . . . My little sister Cassie was bored immediately, and went outside to

play with a dog lying in the shade, one of those typical New Mexico mongrels—but I was transfixed

by the play of wool and hands in that back room of the weaving shop. I went back whenever I

could, the way other kids snuck into bars to play pool or whatever.”

And in Shakespeare the three Fates morphed into the three Weird Sisters—surely no

accident? The witches, too, were shown to “destine, doom,” like the archaic verb form of weird

(after Shakespeare), or “change by witchcraft or sorcery.” Weird had acquired a new power, a causal

thrust; it wasn’t limited to just a done deal, anymore. It was defined as “Having the power to

control destiny/influence fate.” It had become much like a word related to weird in Old

English—weorþan, meaning “to become.” I imagine it related again to the Proto-Indo-European

wértti, “to be turning.”

Being weird, being alive to witchery, could definitely change things, influence the outcome

(or at least the tenor) of a day or life.

—

I’ve written about witchery. About a storm, a great black oak in the foothills above

Stanford, where we lived for ten years:

It is a kind of witching scene, fitful and fateful as Macbeth. But the smell of tandoori spices is

in the house; my charm against the storm, the night, the owl calling unseen in the trees somewhere

nearby, the forces gathering up in the hills with the oak tree.

And then, another time, in a poem, “Koshare,” about an associated kind of magic in the

Southwestern culture I grew up in (and, coincidentally, another storm):

uneasily portentous

like the witches in Macbeth,

the weird sisters,

or koshare, sacred Pueblo clowns—

the black-striped spirit-possessed

mud clowns, Thunderbeings,

fed with melons and tortillas,

innocent and wise

And word magic, always. Discovering as I wrote about the school by the river with its low

roofs, once science labs, my art class digging red clay out of old patches of snow and being taught to

shape heads of quixotic gods, that all those algebraic spells and other sorceries we practiced turned

out not to work, over the years—

I’ve only been able to shape

lopsided gods, with malformed ears

that don’t hear certain prayers,

demanding rituals with owl feathers

in caves I can’t climb to anymore

—until the right words came along, with the transformative power they hold.

And so, over the years between,

I have become a poet.

So I can have those things again

the school in the canyon promised

or at least the possibility—

seeding

the tiny cones of water birch.

Allowing me as a poet, a spinner of words, to become powerful in my own way, become

what becomes me, and hang onto it even when fate’s being more than usually adverse. Words carry

change (as demonstrated in the weird workings of etymology), like destiny, and help me find and

clear my rightful path.

Even if the “becoming” sense of weird was extinct by the 16th century, the old nuance is in it

still, like a paint ghost, a palimpsest, a ghost of self encountered in a far-off place, or a near one, and

fits me to a “T” in both its modern and its ancient guise—deviating from the normal, in order to be.

Going out to find those singular spaces where I belong, the misfit pieces belonging to me.

Soy, Estoy

I’ve just found this excerpt from Toko-pa Turner’s Belonging: Remembering Ourselves Home,

which explains perfectly the difference between fitting in (as I’ve been trying to again, despite myself,

as a changed world urges) and belonging:

“False belonging prefers that we hold our tongue, keep chaos at bay, and perform a

repetitive role that stunts our natural inclination to growth. We may live for a while

in such places, leaving well enough alone. . . . But there is always a threshold at which

we can no longer compromise ourselves. . . . the soul becomes restless.”

And I’ve realized, as I ponder, that the difference described there is more or less exactly the

difference between soy and estoy that I learned back in Spanish class. One’s being, temporarily,

outwardly, inessentially, versus one’s essence or quintessence, one’s quiddity. (The Iberian languages

supposedly the only ones that make this particular distinction between the kinds of “I

am”—Spanish, Portuguese, Catalan, Galician, Basque (though not, Quora.com informs us, Aranese

or other forms of Occitan. I am weird again in wanting to find out these things, and loving those

aberant forms of Occitan).

Many things that might be labeled temporary by quibblers and dogmatists, those without the

poet’s agility in erecting bridges of cloud and spume and inspired surmise, are in fact with me

absolutely—like the recipe for guacamole, sure as any muscle memory, that I’ve made from

Minnesota to Mallorca without faltering at any point. Not my estoy, but purest soy.

The surest thing

I’ve ever done—

ripe avocado

skin rough and pit silky, fitting the palm

bright lemon

stinging just a little in a cut finger

sea salt

a clove of garlic

onion and tomato

crushed red chile, seeds and pods

time

to breathe

time

to become

and then the glazed blue bowl

textured like avocado skin

yielding its alchemy.

No measuring,

just practice, taste,

this ritual I’ve followed

almost all my life

that always brings

a kind of clarity

I’d forget otherwise

and gives me back myself.

Another of my formative experiences was a writing workshop in Mallorca some years ago.

Almost as soon as we landed, like the colors of an old fresco under layers of newer paint, words of

my seventh-grade Spanish began to show spookily through the later overlay of Italian, French. It

was as if they’d been there waiting for me all the while. I hadn’t spoken Spanish for something like

thirty years, but it was the language I learned first and most comprehensively, subjunctive tenses and

all, and there it was again, always—the words rising effortlessly to the surface. Quizás, demasiado,

Londres, izquierdo, estoy. Maybe, too much, London, left-hand, I am (if maybe temporarily).

While I was on the island new words too would keep appearing to me, in their own time, like

the urgent, necessary birds—the hoopoe whose black and white striped feather I found on the road;

swifts, in the valley below; the kind of hawk I named from out of nowhere, and had even as I named

it forgotten again. Kestrel. The hawk that hangs stilled, midair, as if hung up on a ragged splinter of

wind. And then the black falcon the founder of the writing center wrote into her dazzling work, but

I would never see on its own wings.

And all those things are in me, even now, the soy of me, as indelible as the words, the

memory in my bones of quizás and demasiado. Londres, in whatever language it returns. Also my

tenth grade Spanish teacher and the trip she took us on to Albuquerque to the zoo, to claim the sun-

and-shadow-striped zebra, the tram ride up the granite peak named for the watermelon (skymelon,

that color it took on at evening), also in Spanish, and an Indonesian meal with sambal made of

ground chiles—things that are with me, of me, too, here, even or especially on the dullest days, part

of my fabric. Lo que soy.

Tximitxurri

However lost or uncertain I get, however washed out by lengthy periods of fitting in, I’ve

been reminded that I am at heart okay—my weirdness is right there in whatever notebook I carry

with me, always tucked away in that blue canvas bag or another. (One block-printed Pueo, sacred

owl from Hawaii, often as any.) That is the other power of the bag. When I can’t go off visiting

new neighborhoods, exploring the far reaches of the British Museum or lying under Taos Mountain

with windows open reading Henry James, I can write myself there, far far back, away. Back into

being, not just circumspectly fitting in.

“[H]ow wonderful to be who I am,

made out of earth and water,

my own thoughts, my own fingerprints —

all that glorious, temporary stuff.”

(Mary Oliver, from “On Meditating, Sort Of”)

Glorious, temporary stuff. My hard won, precious estoys that together form my soy. Things

that though born of a particular moment and place ground me, serve as my foundations, then add

the turrets and spires and wind-tossed banderoles and gonfalons, embroidered silk.

I am, yo soy, such things as these—

Walking the labyrinth barefoot, to better feel my way. And then the other labyrinth under

the sandstone cliffs on Georgia O’Keeffe’s Ghost Ranch. A third at Stanford, just beyond the spirit

house carved by the New Guinea sculptors during one of my years there.

Speaking French to a young blackbird who has come in answer to my trail of millet and

sunflower seed.

Discovering the Basque tximitxurri, green as delight, translated charmingly as “a mixture of

several things in no particular order.”

Creating my tiny book of hours or of years, hand-stitched by an artist in New Zealand.

Wearing it against my heart like a medicine bundle or spice cabinet, with pinches of my true nature,

my various ventures, quirks, wayward queries.

Some of the precious snatches tucked inside the tiny book, written in copper ink and deep

blue—

lele = flight, to fly

turquoise beads

(Morenci, Smoky Mountain, Candelaria);

limestone sages, and basset horns

the Hawaiians’ twenty-seven kinds of prayer

and Rilke’s “slow descent of aqueducts”

ras el hanout, saffron, turmeric, za’atar

coloring my hands

the shop of pigments and green chalk in Bloomsbury;

chilaquiles, the River Song in the San Gabriel Valley

glass beads given as offerings

like the dictionary words,

sea-polished, secreted away

(ankh, annul, anole)

Not a Disaster

I am still sad, far from England and all the other far places I love, missing my life as Clarice

Lispector describes it perfectly—

“I miss everything that marked my life. ... I miss the things I lived and the ones I let go. ...

How many times I want to find I don’t know what... I don’t know where... To rescue something

I don’t know what it is or where I lost it.”

But I have understood, putting the recent feeling of loss down in words, in the same

notebook that now holds the little beach, the cardamom, the dogwalkers, the Sterling Silver “wishy-

washy” ink I find today along with letters from Emily Dickinson translated charmingly into Italian,

that I’m still me, enduringly, even at this remove. Still weird as weird can be. That the whorls of

labyrinths, like fingerprints, are uniquely and indelibly mine.

The notebook holds the poem that a friend sent me when I first mentioned sitting on that

bench above the beach with my beloved incongruous London Review of Books bag. A poem

recounting another writer’s similar realization.

“I lost two cities, lovely ones. And, vaster,

some realms I owned, two rivers, a continent.”

Elizabeth Bishop mourns losses too, but in the end dismisses them with a kind of wistful

defiance—“I miss them, but it wasn’t a disaster.”

Perhaps, laying her pen down, she concluded as I have that despite thefts and compromises,

drawings-in of time and space and opportunities, it’s possible through words (containing realms, and

multitudes) to carry on, even triumph. If the places themselves can no longer keep me ebulliently

wayward, if I have lost those distant cities with their lilac-haunted squares, and the again forbidden

towns with turquoise doors in old mud-colored walls, I can still hope to come upon myself in the

regenerative neighborhoods of paper, pigments, ink.

Christie Cochrell's work has been published by Catamaran, Lowestoft Chronicle, Cumberland River Review, Tin House, and a variety of others, receiving several awards and Pushcart Prize nominations. Chosen as New Mexico Young Poet of the Year while growing up in Santa Fe, she's recently published a volume of collected poems, Contagious Magic. She lives by the ocean in Santa Cruz, California—too often lured away from her writing by otters, pelicans, and seaside walks.